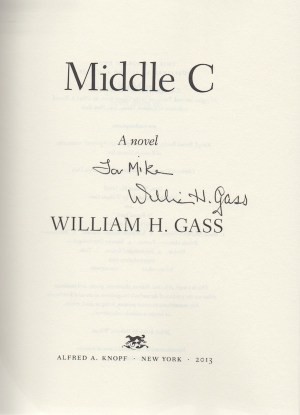

Last Tuesday I made my way to Left Bank Books, a St. Louis favorite, to listen to William Gass read from his newest book, Middle C

Last Tuesday I made my way to Left Bank Books, a St. Louis favorite, to listen to William Gass read from his newest book, Middle C. As some readers may know, I am a fan, or maybe even a connoisseur of post-apocalyptic fiction; thus Gass really caught my attention when he read one of the most searing scenes of apocalypse survival I’ve ever encountered, something that makes most works in the post-apocalyptic genre seem exuberantly upbeat.

While this scene is not written as a poem, it is one long sentence written with the attention to cadence and sound that you expect of poetry, and so it qualifies for this week’s Sunday Poem. As for a possible science-related theme, aside from the association I see with my favorite subgenre of science fiction, this passage from Middle C describes the narrator’s speculation that the human species will somehow, despite losing Armageddon, squeak through with its fundamental biological drive to reproduce intact. Continue reading “Sunday Science Poem: Reproduction will beat Armageddon”

The purpose of the

The purpose of the

For those of you looking for a break from the pre-game show, here’s this week’s reading of

For those of you looking for a break from the pre-game show, here’s this week’s reading of