Mary Shelley’s The Last Man (1826)

Not all post-apocalyptic fiction is about death. That might seem odd, given the high death toll in this genre. But most of it is about something else, like nature, war, technology, civilization, or even religion. Mary Shelley’s The Last Man is an exception: it is a book about death.

Not all post-apocalyptic fiction is about death. That might seem odd, given the high death toll in this genre. But most of it is about something else, like nature, war, technology, civilization, or even religion. Mary Shelley’s The Last Man is an exception: it is a book about death.

And death is what saves it from being just another 19th century door-stopper, doomed to bore contemporary readers. Shelley did what, as far as I know, no other writer in the genre has done. She turned her personal grief into the End of the World. In the Last Man, the deaths of her husband, her children, and her friends are transformed into the complete extinction of the human species. Continue reading “End of the World, 1826: Mary Shelley’s The Last Man”

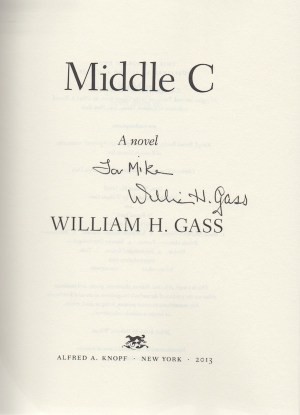

Long-time readers know I’m a fan of

Long-time readers know I’m a fan of  Last Tuesday I made my way to Left Bank Books, a St. Louis favorite,

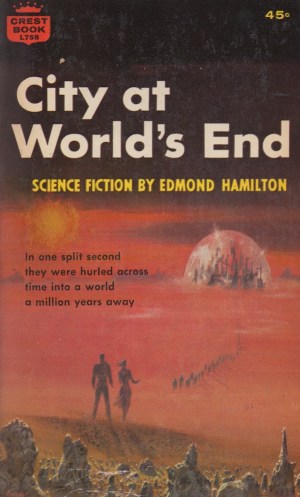

Last Tuesday I made my way to Left Bank Books, a St. Louis favorite,  Within science fiction, there is a great tradition of the oddball post-apocalyptic novel, pioneered by Philip Dick in Dr. Bloodmoney (1965) and Deus Irae (with Roger Zelazny, 1976). It is a tradition still thriving today in books like Jonathan Lethem’s Amnesia Moon (1995) and Ryna Boudinot’s Blueprints of the Afterlife (2012), and it includes Denis Johnson’s lyrical Fiskadoro. The oddball post-apocalyptic novel is not concerned with the gritty realities of survival; instead, it takes place in a less lethal and much more hallucinatory setting that is populated with various hucksters, grotesques, dreamers, and generally confused people who are trying to figure out just what the hell is going on.

Within science fiction, there is a great tradition of the oddball post-apocalyptic novel, pioneered by Philip Dick in Dr. Bloodmoney (1965) and Deus Irae (with Roger Zelazny, 1976). It is a tradition still thriving today in books like Jonathan Lethem’s Amnesia Moon (1995) and Ryna Boudinot’s Blueprints of the Afterlife (2012), and it includes Denis Johnson’s lyrical Fiskadoro. The oddball post-apocalyptic novel is not concerned with the gritty realities of survival; instead, it takes place in a less lethal and much more hallucinatory setting that is populated with various hucksters, grotesques, dreamers, and generally confused people who are trying to figure out just what the hell is going on. On March 1st, 1954, on the Bikini atoll of the Marshall Islands, U.S. scientists detonated a thermonuclear hydrogen bomb called Castle Bravo. The expected yield of Bravo was five megatons TNT, but the scientists had missed a crucial fusion reaction that took place in this particular bomb design. As one scientist

On March 1st, 1954, on the Bikini atoll of the Marshall Islands, U.S. scientists detonated a thermonuclear hydrogen bomb called Castle Bravo. The expected yield of Bravo was five megatons TNT, but the scientists had missed a crucial fusion reaction that took place in this particular bomb design. As one scientist