H.G. Wells’ The War in the Air (1908)

After the First World War, as historian Barbara Tuchman wrote in her landmark history of the pre-war years, “illusions and enthusiasms possible up to 1914 slowly sank beneath a sea of mass disillusionment.” But there were some who were disillusioned long before that. In the decades leading up to the catastrophic conflict, all sorts of writers and thinkers worried about the possibility of a worldwide war, fought with technologies that were capable of causing destruction on an entirely new scale.

After the First World War, as historian Barbara Tuchman wrote in her landmark history of the pre-war years, “illusions and enthusiasms possible up to 1914 slowly sank beneath a sea of mass disillusionment.” But there were some who were disillusioned long before that. In the decades leading up to the catastrophic conflict, all sorts of writers and thinkers worried about the possibility of a worldwide war, fought with technologies that were capable of causing destruction on an entirely new scale.

Concerns about a massive conflict were so serious that the major European powers held two peace conferences, in 1899 and 1907, despite the fact that they weren’t currently at war with each other. Fiction writers captured the martial zeitgeist with a steady stream of future war stories (including H.G. Wells’ 1898 The War of the Worlds), exploring military possibilities that would soon be realized.

The most bitingly clear statement of pre-war anticipation and disillusionment is H.G. Wells’ 1908 novel, The War in the Air. The book is a major genre milestone, one that explicitly lays out an important theme of the coming century: Our civilization is headed for a catastrophic end unless our moral progress keeps pace with our technological process.

CIVILIZATION AND ITS DISCONENTS

Wells’ theme should sound familiar to anyone who has read a nuclear holocaust novel. With great scientific progress comes great progress in our ability to destroy ourselves. The books narrator explains how such progress led up to the apocalyptic War in the Air:

For three hundred years and more the long, steadily accelerated diastole of Europeanized civilization had been in progress: towns had been multiplying, populations increasing, values rising, new countries developing; thought, literature, knowledge unfolding and spreading. It seemed but a part of the process that every year the instruments of war were vaster and more powerful, and that armies and explosives outgrew all other growing things….

Three hundred years of diastole, and then came the swift and unexpected systole, like the closing of a fist.

The War in the Air tells the story of this “unexpected systole” through the eyes of Bert Smallways, an Everyman who stumbles into the center of war. Bert is “a vulgar little creature, the sort of pert, limited soul that the old civilization of the early twentieth century produced by the million in every country of the world.” He is an unsuccessful go-getter, living in the provincial, south English town of Bun Hill. As Bert moves from one failed venture to another, the world changes rapidly in the background. Traditional railways are replaced by that perennial symbol of misguided progress, the monorail. And one day, an inventor named Butteridge finally figures out how to make a successful flying machine. Bert witnesses its virgin flight.

The War in the Air tells the story of this “unexpected systole” through the eyes of Bert Smallways, an Everyman who stumbles into the center of war. Bert is “a vulgar little creature, the sort of pert, limited soul that the old civilization of the early twentieth century produced by the million in every country of the world.” He is an unsuccessful go-getter, living in the provincial, south English town of Bun Hill. As Bert moves from one failed venture to another, the world changes rapidly in the background. Traditional railways are replaced by that perennial symbol of misguided progress, the monorail. And one day, an inventor named Butteridge finally figures out how to make a successful flying machine. Bert witnesses its virgin flight.

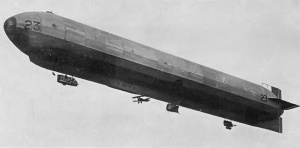

One thing follows another, and through an accident Bert finds himself alone in a hot air balloon with the secret plans for Butteridge’s flying machine. He lands in Germany, near a top-secret fleet of airships that are about to set sail for a surprise attack on America. After trying to pass himself off as Butteridge and making an offer to sell his secret plans, Bert ends up on the flagship of the German air fleet when the War in the Air breaks out.

THE END OF THE HALLUCINATION OF SECURITY

Wells works through the new logic of total war. It turns out that all nations were secretly building fleets of airships. The airships, slow and difficult to maneuver, are not particularly effective against each other, but they are great at bombing cities. And so each side tries to win the war by laying waste to the other side’s cities. The inevitable happens: Civilization collapses as the world bombs itself back to the Middle Ages.

Bert stumbles through it all, with very little control over his fate. He eventually works his way home, across a classic post-apocalyptic landscape, where he becomes a leader of his small community by being more violent than the next guy.

Bert’s story is replayed again and again in subsequent post-apocalyptic fiction. Fortunately for us, two world wars didn’t lead to the total collapse of human civilization. But they were immediately followed by the threat of nuclear holocaust. And today, the potentially existential threat of catastrophic climate change raises the same question that drives these apocalyptic war stories: Can we ever control ourselves as well as we can control nature?

Bert’s story is replayed again and again in subsequent post-apocalyptic fiction. Fortunately for us, two world wars didn’t lead to the total collapse of human civilization. But they were immediately followed by the threat of nuclear holocaust. And today, the potentially existential threat of catastrophic climate change raises the same question that drives these apocalyptic war stories: Can we ever control ourselves as well as we can control nature?

In Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud famously summed up the tension between our mastery of nature and our own uncontrolled natures:

The fateful question for the human species seems to me to be whether and to what extent their cultural development will succeed in mastering the disturbance of their communal life by the human instinct of aggression and self-destruction… Men have gained control over the forces of nature to such an extent that with their help they would have no difficulty in exterminating one another to the last man.

Freud was writing after the catastrophic experiences of one war, and as the next one was already brewing. Two decades earlier, during a time of remarkable peace, prosperity, and technical progress, Wells posed the same question and expressed is pessimism about the answer. As his narrator says, looking back from the distant future:

When now in retrospect the thoughtful observer surveys the intellectual history of this time, when one reads its surviving fragments of literature, its scraps of political oratory, the few small voices that chance has selected out of a thousand million utterances to speak to later days, the most striking thing of all this web of wisdom and error is surely that hallucination of security. To men living in our present world state, orderly, scientific and secured, nothing seems so precarious, so giddily dangerous, as the fabric of the social order with which the men of the opening of the twentieth century were content.

Image credits: HM AR 23 Airship with Camel, Imperial War Museum, picture scanned by Ian Dunster June 1973 issue of Aeroplane Monthly, via Wikimedia Commons; Monorail (1907), public domain, via Wikimedia Commons; “German Airship bombing Warsaw in 1914” by Hans Rudolf Schulze, via Wikimedia Commons.

Read more entries in my post-apocalyptic science fiction series, and my other science fiction reviews.