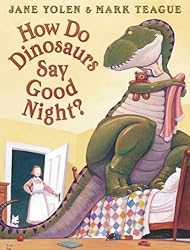

One of the new picture books making the bedtime rounds at our house is How Do Dinosaurs Say Goodnight?, which describes and depicts dinosaurs doing such un-dinosaurly things as tucking themselves into bed or kissing their human mothers good night. The book is whimsical, gorgeously illustrated, and includes a scientific angle, as the genus names of the dinosaurs are included in the pictures. I’m always careful to read these genus names aloud as we look at each picture. But is this book actually teaching my daughter anything about dinosaurs? And does the misinformation get in the way of her learning these facts? A new study suggests that it might.

One of the new picture books making the bedtime rounds at our house is How Do Dinosaurs Say Goodnight?, which describes and depicts dinosaurs doing such un-dinosaurly things as tucking themselves into bed or kissing their human mothers good night. The book is whimsical, gorgeously illustrated, and includes a scientific angle, as the genus names of the dinosaurs are included in the pictures. I’m always careful to read these genus names aloud as we look at each picture. But is this book actually teaching my daughter anything about dinosaurs? And does the misinformation get in the way of her learning these facts? A new study suggests that it might.

Picture books that anthropomorphize animals – and even inanimate objects – are the norm rather than the exception. These books are fanciful and fun. They depict worlds like our own but different in magical ways that delight children and adults alike. Perhaps these books are more engaging for young children than realistic books, thus fostering lifelong reading habits. Perhaps they stimulate a child’s blossoming imagination. Perhaps – although I would argue that the true story of our diverse, teeming planet is more remarkable than your average talking teddy bear or hippo in a swimsuit.

Look at it this way: everything we do is meant to prepare our children for life in this complex and befuddling world. Why, then, do we feed them so much distorted, inaccurate information? How are they supposed to know what is real and what is fantasy? How is my daughter supposed to know that the three-horned dinosaur was called Triceratops but that it never coexisted with humans nor stomped on its hind legs to protest bedtime?

Researchers in Boston and Toronto looked into this issue and recently published their findings in Frontiers in Psychology. The scientists created picture books based on three animals species that are relatively unknown among North American children: cavies, oxpeckers, and handfish. Their study consisted of two separate experiments. For the first experiment, all of the books featured factual illustrations of the animals, but for each animal the authors made one version of the book with realistic text and one version with text that depicted the animals as human-like. Here are two examples:

Realistic

When the mother cavy wakes up, she usually eats lots of grass and other plants.

Then the mother cavy feeds her baby cavies.

Mother cavy also licks the babies’ fur to keep them clean.

Mother cavy and her babies spend the rest of the day lying in the sun.

At night, they sleep in a small cave.

After they go to sleep, mother cavy’s big ears help her hear noises around her.

Anthropomorphic

“Yum, those grass and plants are delicious!” Mother cavy thinks as she eats her breakfast.

“I will feed some to my baby cavies too!” she says.

The baby cavies love to play in the grass! But they’ve gotten all dirty! “Time for your bath,” Mother cavy says.

Mother cavy and her babies like to spend the afternoon sunbathing.

At night, Mother cavy tucks her babies in to bed in a small cave. “Mom, I’m scared!” says the baby cavy.

“Don’t be afraid,” she says. “I’ll listen for noises with my big ears and keep us safe.”

Children ages 3 to 5 years old were randomly assigned to read the books with either the factual or fantasy text. After children read one of these books with an experimenter, a second experimenter showed them a picture of the real animal described the story and asked the kids questions about it. Do cavies eat grass? Do cavies talk? Some of these questions tested the factual information kids took away from the picture book, while others tested how much the children anthropomorphized the animal. The children who read the books with talking animals were more likely to say those animals really talk than were children who read the versions with factual text. Still, the two groups were roughly equal in the factual information they retained about the animals.

For the second experiment, the researchers again made two versions of picture books for each animal. This time, both versions showed the animals dressed in clothes, sitting at tables, or engaged in other human activities. As before, the researchers made two versions of each book: one with factual text and one that anthropomorphized the animals. The children who read the fully anthropomorphized picture books tended to believe that the animals really engage in human behaviors like speech. These kids also answered fewer factual questions about the animals correctly (compared with the children who read factual text paired with the fantastical pictures).

These findings have two major implications. First, picture books that anthropomorphize animals seem to actually teach children that animals think and behave like humans. In one sense you might say this is good, as it could discourage animal cruelty and abuse. But in another sense, it’s highly unproductive. At the very best, children will have to unlearn all of this nonsense. At worst, they will carry some of this misinformation about the natural world throughout life – probably not as a belief in talking animals, but in the assumptions they make about the thoughts, feelings, and intentions of other species.

The other takeaway is that the whimsical aspects of a picture book may be sabotaging your child’s learning of the real information in these stories, particularly when the illustrations and text both reflect fantasy. Since children can’t conclusively tell fact from fiction, some may be discounting all information from highly fanciful stories – including incredible-yet-true facts like the chameleon’s mercurial skin tone or the transformation of caterpillar into butterfly. As the authors write in their paper: “if the goal of the picture book interaction is to teach children information about the world, it is best to use books that depict the world in a realistic rather than fantastical manner.” Of course that takes enthusiasm out of the equation. What kid would sit for hours watching videos of real trains when he or she could watch Thomas? Human narrative adds interest, but it also seems to muddle up real learning, at least in preschoolers.

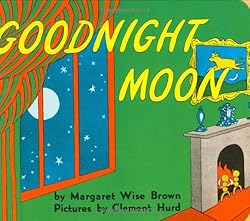

I hate to build an argument against imaginative, fanciful picture books. What am I, Scrooge? But while I love imagination, I don’t love misinformation – particularly scientific misinformation. And while I love magic, I don’t love magical thinking or flawed reasoning about the natural world.  I’m not saying you should throw away your copy of Goodnight Moon and all things Sandra Boynton – just keep in mind that wee ones don’t always know real from fanciful or facetious. Talk about these concepts with them. Buy some nonfiction picture books with accurate information about animals and keep them in the lineup. And know that, for all your efforts, they may come away believing that trains talk and bunnies knit . . . at least for now.

I’m not saying you should throw away your copy of Goodnight Moon and all things Sandra Boynton – just keep in mind that wee ones don’t always know real from fanciful or facetious. Talk about these concepts with them. Buy some nonfiction picture books with accurate information about animals and keep them in the lineup. And know that, for all your efforts, they may come away believing that trains talk and bunnies knit . . . at least for now.

The original version of this post appeared on Rebecca Schwarzlose’s personal, neuroscience blog Garden of the Mind.

I wonder if the issue isn’t so much exposure to fictional, talking animals as it is non-exposure to real, non-talking animals.

Yes, that’s definitely a factor! The authors specify that the kids in the experiment were urban children, since rural children with more experience with animals have been shown to anthropomorphize animals less.

I’ve always understood,

Young children engage in magical thinking,

As they process the world,

Correct me if I am in fact mistaken.

http://www.scholastic.com/teachers/article/ages-stages-how-children-use-magical-thinking

They sure do. Even adults engage in magical thinking sometimes. Magical thinking has more to do with why someone believes things happen than what he/she believes happens. But if you’re referring to belief in magical occurrences (like animals having a chat), it’s hardly surprising that young children get confused. To them, cell phones and airplanes may seems as magical and implausible as talking animals and flying carpets. It’s only through experience with the world and its norms that they can make such distinctions. What I’m saying in the post is that, in addition to all their virtues, fanciful children’s books (and movies) may be making those distinctions more challenging for children at a certain age of development.

What you say makes real sense,

Although, I don’t trust myself,

As my sense of sense is likely to be wrong,

I’ll trust prevailling wisdom,

That tried and true consensus,

But, then again, I don’t know what that is,

I’m thinking of my daughter,

I’ve gotta do right by ‘er,

Oh, what the hell, we got us the museum.