I recently heard a presentation by the Caltech biophysicist Rob Phillips, in which he issued a challenge to those who claim biology, in contrast to physics, is too complex and messy to be understood with mathematical theories: take a look at Tycho Brahe’s 16th century astronomical data, and see if you can make sense of it without math. Take a look at the data, and see if you can demonstrate, without a mathematical theory, that the orbit of Mars is an ellipse.*

I recently heard a presentation by the Caltech biophysicist Rob Phillips, in which he issued a challenge to those who claim biology, in contrast to physics, is too complex and messy to be understood with mathematical theories: take a look at Tycho Brahe’s 16th century astronomical data, and see if you can make sense of it without math. Take a look at the data, and see if you can demonstrate, without a mathematical theory, that the orbit of Mars is an ellipse.*

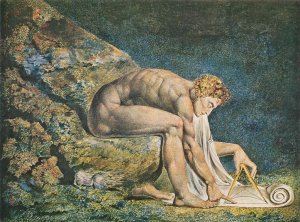

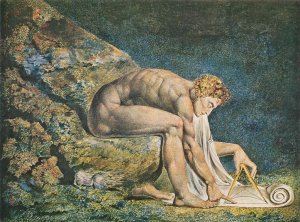

In order to understand the messy real world, scientists use abstractions that can be quite distant from our everyday experiences. The historians of science Stephen Toulmin and June Goodfield explain how this was crucial to Newton’s method:

[W]here Aristotle’s theory of motion was based on familiar, everyday principles, Newton’s was stated in terms of abstract mathematical ideals. The circling heavens, a falling stone, smoke rising from a fire, the steady progress of a horse and cart: these were the objects by comparison with which Aristotle explained other kinds of motions. For Newton, on the other hand, the explanatory paradigm was a kind of motion we never encounter in real life. Nothing ever actually moves uniformly and free of all forces, at a steady speed and in a constant Euclidian direction. Yet Newton was able to bring together the threads left loose by his predecessors by systematically applying just this abstract idea of ‘natural’ motion. So far from being guided by experience alone, he could not afford to be too much tied down to the evidence of his senses, or to the results of experiments: it was, rather Aristotle who stuck too closely to the facts. Newton was ready to imagine something which was practically impossible and treat that as his theoretical ideal.

Musicians, artists, and poets have also found that abstraction is crucial. The abstract features make it tough for most of us to grasp modern works. Jacques Barzun explained it this way:

Like the would-be purist in art, the scientist takes a concrete experience and by an act of abstraction brings out a principle that may have no resemblance to the visible world… Poets and prosaists, whether Abolitionist, Decadent, or Symbolist, found that to create works adequate to their vision the language must be recreated.

If we recognize the common role of abstraction in art and in science, the baffling poetry of someone like Arthur Rimbaud begins to make much more sense.

Continue reading “Sunday Science Poem: Abstraction is crucial in science and poetry”

Science works by making models of the world. We need models, because the data rarely speak for themselves.

Science works by making models of the world. We need models, because the data rarely speak for themselves.

For at least a millennium in the West, Christianity was the dominant public perspective on how the world operates. That is no longer true. In our culture, science now explains the world.

For at least a millennium in the West, Christianity was the dominant public perspective on how the world operates. That is no longer true. In our culture, science now explains the world.  With the

With the

I recently heard a presentation by the Caltech biophysicist Rob Phillips, in which he issued a challenge to those who claim biology, in contrast to physics, is too complex and messy to be understood with mathematical theories: take a look at Tycho Brahe’s 16th century astronomical data, and see if you can make sense of it without math. Take a look at

I recently heard a presentation by the Caltech biophysicist Rob Phillips, in which he issued a challenge to those who claim biology, in contrast to physics, is too complex and messy to be understood with mathematical theories: take a look at Tycho Brahe’s 16th century astronomical data, and see if you can make sense of it without math. Take a look at