Garrett P. Serviss’ The Second Deluge (1912)

1912 was a good year for science fiction — according to some, it was the best year. Certainly for pulp science fiction, it was a landmark year. Although the first dedicated pulp SF magazine, Amazing Stories, wouldn’t appear for more than a decade, two of the foundational texts of pulp SF were published in 1912: Edgar Rice Burroughs’ A Princess of Mars, which began as the serial “Under the Moons of Mars” in February, and Hugo Gernsback’s Ralph 124C 41+, whose last installment was published in March.

1912 was a good year for science fiction — according to some, it was the best year. Certainly for pulp science fiction, it was a landmark year. Although the first dedicated pulp SF magazine, Amazing Stories, wouldn’t appear for more than a decade, two of the foundational texts of pulp SF were published in 1912: Edgar Rice Burroughs’ A Princess of Mars, which began as the serial “Under the Moons of Mars” in February, and Hugo Gernsback’s Ralph 124C 41+, whose last installment was published in March.

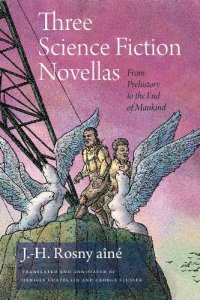

Another contributor to this early pulp ferment, less memorable than Burroughs or Gernsback, was the American journalist Garrett Serviss. Serviss was a popular science writer who had also written an 1898 sequel to Wells’ War of the Worlds, featuring an invasion of Mars led by none other than Thomas Alva Edison. The Second Deluge, serialized in 1911-12, is a pulpy, early instance of a classic storyline that crops up over and over again post-apocalyptic fiction: Noah’s Ark. Continue reading “Apocalypse 1912: Salvation Through Faith in Science”

As I

As I  After the First World War, as historian Barbara Tuchman wrote in her

After the First World War, as historian Barbara Tuchman wrote in her

The Doomsman opens in what seems to be the primitive past: A young man sits on the shore of a bay, dressed in a tunic. In the forest behind him are the heavy wooden walls of a stockade, a clue to the defensive nature of life in this sparsely inhabited country. But not everything fits. The young man is looking across the bay at a vague, dark outline of some tall structure, while in his hands he holds a book: A Child’s History of the United States. He is sitting on the shores of New York, looking out at what’s left of Manhattan.

The Doomsman opens in what seems to be the primitive past: A young man sits on the shore of a bay, dressed in a tunic. In the forest behind him are the heavy wooden walls of a stockade, a clue to the defensive nature of life in this sparsely inhabited country. But not everything fits. The young man is looking across the bay at a vague, dark outline of some tall structure, while in his hands he holds a book: A Child’s History of the United States. He is sitting on the shores of New York, looking out at what’s left of Manhattan.