“American SF by the mid-1950’s was a kind of jazz, stories built by riffing on stories. The conversation they formed might be forbiddingly hermetic, if it hadn’t been quickly incorporated by Rod Sterling and Marvel Comics and Steven Spielberg (among many others) to become one of the prime vocabularies of our age.”

So writes Jonathen Lethem in his introduction to The Selected Stories of Philip K Dick. If you’re looking for that sci-fi conversation at its most hermetic, go read the 1956 celebratory anthology, The Best From Fantasy and Science Fiction, Fifth Series. The collection reads like a series of bad inside jokes, although three stories make it worth the $2.50 I paid for it at my favorite source of vintage sci-fi. (Check out the full listing of this anthology at isfdb.org.)

So where did this collection go wrong? Continue reading “Inside the 50’s science fiction bubble”

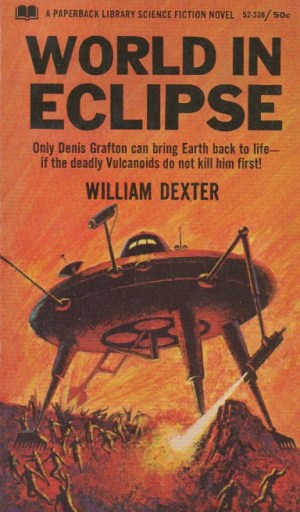

World in Eclipse is a mildly entertaining but second-rate

World in Eclipse is a mildly entertaining but second-rate