The possibility of human extinction in End of the World sci-fi is sometimes paired with a consideration of our next evolutionary step – a concept that is less scientific than it sounds (evolution shouldn’t be considered in such linear terms), but one that does make an effective fictional tool for thinking about human impermanence.

The possibility of human extinction in End of the World sci-fi is sometimes paired with a consideration of our next evolutionary step – a concept that is less scientific than it sounds (evolution shouldn’t be considered in such linear terms), but one that does make an effective fictional tool for thinking about human impermanence.

Arthur C. Clarke’s majestic Childhood’s End is about the end of Homo sapiens and evolutionary succession, in a sense. In this case the end of the human species doens’t occur as a result of nuclear annihilation or an asteroid stike, and our evolutionary successors don’t emerge from a struggling population of mutant survivors. The end here comes through a double transcendence. Our species leaves behind its childhood in a way that reveals our relationship to nature in its most universal form, and to science and rationality, which prove not only more powerful than our wildest imaginings, but also, paradoxically, small and limiting in the larger scheme.

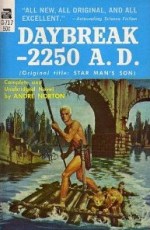

I’ve read three 1952 post-apocalyptic novels for this

I’ve read three 1952 post-apocalyptic novels for this