John Ames Mitchell’s The Last American (1889)

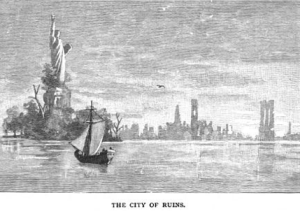

Images of a run-down Statue of Liberty against a backdrop of decaying New York are a staple of science fiction. So are visions of a post-apocalyptic Washington D.C. As I’ve noted before, the fascination with ruin porn dates back to at least the late 18th century. But America was a backwater at the time – the New World (or the Western presence there anyway) was too new to ruin in futuristic visions. The very first work of science fiction set against a backdrop of ruined, major U.S. cities, as far as I can find, is the brief 1889 satire, The Last American: A fragment from the journal of KHAN-LI, Prince of Dimph-yoo-chur and Admiral in the Persian Navy, by the original publisher of LIFE magazine, John Ames Mitchell.

Images of a run-down Statue of Liberty against a backdrop of decaying New York are a staple of science fiction. So are visions of a post-apocalyptic Washington D.C. As I’ve noted before, the fascination with ruin porn dates back to at least the late 18th century. But America was a backwater at the time – the New World (or the Western presence there anyway) was too new to ruin in futuristic visions. The very first work of science fiction set against a backdrop of ruined, major U.S. cities, as far as I can find, is the brief 1889 satire, The Last American: A fragment from the journal of KHAN-LI, Prince of Dimph-yoo-chur and Admiral in the Persian Navy, by the original publisher of LIFE magazine, John Ames Mitchell.

The book, as the title indicates, is presented as an excerpt from the journal of a Persian Naval admiral, who with his crew stumbles into New York’s harbor 1000 years after America’s demise in 1990. The Persians, who have mocking names like Nofuhl , Lev-el-Hedyd, and Ad-el-pate, comment on the follies of the lost civilization, while they themselves are portrayed as superstitious primitives who make the ancient “Mehrikans” look good by comparison. The Last American reads like a very mediocre Mark Twain — A Connecticut Yankee, published the same year, leaves Mitchell’s book in the dust. Nevertheless, Mitchell, who was surely influenced by After London, made an important contribution to the genre: satire. Continue reading “New World Apocalypse 1889: The Last American”

Gothic and Romantic writers — like

Gothic and Romantic writers — like  The word “apocalypse” not only means a cataclysm that ends the current world order, but also, from the word’s Greek root, a revelation of truth. Poe’s very short story about the End of the World is an apocalypse in both senses of the word. In this early instance of the cataclysmic-collision-with-celestial-object tale, Poe makes an odd mix of science and prophesy to capture the moment of “the speculative Future merged in the august and certain Present.”

The word “apocalypse” not only means a cataclysm that ends the current world order, but also, from the word’s Greek root, a revelation of truth. Poe’s very short story about the End of the World is an apocalypse in both senses of the word. In this early instance of the cataclysmic-collision-with-celestial-object tale, Poe makes an odd mix of science and prophesy to capture the moment of “the speculative Future merged in the august and certain Present.”  Not all post-apocalyptic fiction is about death. That might seem odd, given the high death toll in this genre. But most of it is about something else, like nature, war, technology, civilization, or even

Not all post-apocalyptic fiction is about death. That might seem odd, given the high death toll in this genre. But most of it is about something else, like nature, war, technology, civilization, or even