Rage against the machine

It’s the post-apocalyptic 1990’s, thanks to a late 70’s nuclear third world war brought on by the giant computers that had been delegated by humans to handle geopolitics. (They sound a little like the micro-trading computers that now handle the much of high finance.) It turns out that the computers weren’t any better at keeping the peace than humans were.

It’s the post-apocalyptic 1990’s, thanks to a late 70’s nuclear third world war brought on by the giant computers that had been delegated by humans to handle geopolitics. (They sound a little like the micro-trading computers that now handle the much of high finance.) It turns out that the computers weren’t any better at keeping the peace than humans were.

Neurosurgeon and former Mormon Dr. Martine has spent the last 18 post-war years hiding out on an uncharted island somewhere in the Indian Ocean, integrated with the natives, but events draw him back home to what’s left of the United States. What he finds, built upon the slag heaps of both the former United States and Soviet Union, is a cyborg civilization filled with men who’ve renounced war, cut off their limbs, and replaced them with nuclear-powered prostheses. To his shock, Martine find out that he unwittingly had something to do with this bizarre state of affairs.

Bernard Wolfe’s 1952 Limbo is a disturbing but weirdly compelling proto-cyberpunk behemoth that combines an edgy, in-your-face language that compares with the best of Alfred Bester, with long, Heinlein-style philosophical digressions that are about as subtle as a kick to the head, to create one long, entertaining rant against… well, something, but I couldn’t quite figure out what.

The Plotline:

Escaping World War III, Dr Martine has gone native, living with an island people, the Mandunji, who have come up with a primitive form of lobotomy to control members of their society considered anti-social. Martine has used his skills in neurosurgery to help the lobotomies become less fatal. He’s torn about his role, because he is basically excising all motivation, drive, and pleasure from these people. That’s because Martine finds that aggression, sexual desire, and the drive to achieve are all tied up somehow in the same neurological structures, and you can’t kill one without the other.

After 18 years on the island, events draw Martine back to the remains of the United States, where men of status (and only men) seem to have bought into the same philosophy as the islanders – after the horrors of nuclear war, these people have decided to literally disarm, by voluntarily having their limbs amputated. This move is supposed to tame aggression, but in most cases the amputated limbs have been replaced by nuclear-powered, super-featured prostheses that enable their wearers to leap tall buildings in a single bound. Martine spends much of the book mulling over the philosophy behind this shocking movement, but for the moment, it seems to have achieved peace. The Soviets have moved in the same direction, and, in order to further dissipate tensions, the Russians and the Americans get together periodically to hold a cyborg olympics.

But not all is well in this society. Amputation and prostheses are status symbols, typically only available to men, and white men at that. An essential material used in the nuclear-powered prostheses is available in limited supply, which means that geopolitical tensions between the Americans and the Russians are on the rise. Naturally, there is a fundamentalist sect of amputation, men who cut it all off and refuse to become cyborgs. They remain in a state of helplessness, having every last disgusting need attended to by their women, who also push these total amputees around in baby strollers. No Freudian overtones here, of course.

Deep Thoughts

Much of the book is drenched in overt philosophical references that don’t really come together into anything coherent. Wolfe lists many of his influences in an epilogue to the book: Freud, of course, Norbert Wiener, Dostoevsky, Max Weber, William James, Nietzsche, Masochism in Modern Man, Tolstoy, and Lawrence Stern. And the result is exactly what you’d expect, except that Wolfe can write such entertaining riffs that you wade through this heavy mashup amazed that Wolfe is actually pulling it off. Most of the philosophical discussion gets at the question of humanity’s aggression – what does it mean, where does it come from, how do you get rid of it without turning humans into helpless, sexually impotent infants?

Aggression seems to be intimately tied to technology, not a surprising view for a post-apocalyptic book written in the early 50’s. Technology is a result of our restless, aggressive, sexual drive, and it also ends up becoming the means of aggression. What Martine concludes, although I can’t retrace the line of reasoning that leads him here, is that all of our aggression is basically a manifestation of feelings of masochism. Our assaults on others are really just an assault on ourselves. The cyborgs of limbo are clearly a manifestation of our complicated relationship with technology – amputated limbs can no longer wield weapons, but prosthetic limbs can become weapons. Subtle? No, but Wolfe succeeds because he basically thinks aloud through the book, and compellingly expresses the anguish he feels over our inability to cleanly resolve the tangled connections between our technology and our desires. Wolfe, during the early post-war years of scientific triumph, and in a genre filled with unabashed cheerleading for technology as a panacea, was giving voice to doubts and ambiguities that would later become a feature of New Wave sci-fi and cyberpunk. For this reason, Limbo is one of the essential post-apocalyptic novels of the 1950’s.

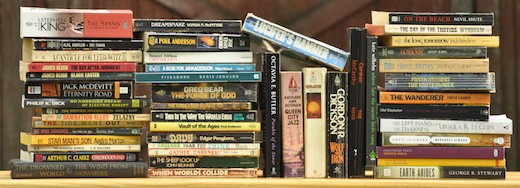

Stay tuned for more reviews in my survey of 60+ years of post-apocalyptic fiction.

You beat me to it!! I’ve wanted to review this for a long long long time!

Thanks for the great review.

Thanks for reading. This book left me more confused than not, but it’s a key, influential work.