J.-H. Rosny aîné’s The Death of the Earth (1910)

As I wrote when I first began this series on post-apocalyptic science fiction, what makes this genre so compelling is how its writers put our mastery of nature up against the possibility of human extinction. The extinction of a species is a routine event, and has been for the entire history of life on earth. So what about us? Will our species eventually disappear, or will our mastery of science and technology protect us from nature’s ruthless assaults?

As I wrote when I first began this series on post-apocalyptic science fiction, what makes this genre so compelling is how its writers put our mastery of nature up against the possibility of human extinction. The extinction of a species is a routine event, and has been for the entire history of life on earth. So what about us? Will our species eventually disappear, or will our mastery of science and technology protect us from nature’s ruthless assaults?

This theme is beautifully explored by one of the early masters of science fiction, the Belgian writer J.-H. Rosny aîné. Rosny, whose career began in the 1880’s and ended with his death during the Campbellian Golden Age, can be considered the father of hard science fiction because, as his translators argue, unlike Verne or Wells, he “was the first writer to allow science to write his narratives” from a “neutral, ahumanistic” perspective.

In this way, Rosny is much like the scientifically realist Camille Flammarion; but unlike Flammarion, Rosny’s purpose is novelistic rather than didactic. The result is fiction that is as compelling as that of Verne or Wells, told in a detached, analytic style that makes Rosny’s voice unique in early SF. This voice has a powerful effect in The Death of the Earth, a ruthless evolutionary vision of human extinction, in which our species cedes the planet to a completely new form of life.

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF EXTINCTION

The Death of the Earth is in many ways a secular version of the biblically-themed, original Last Man story: The aging earth is no longer a fertile habitat for humans, and the remaining population has to confront the fact that they are facing the end. In Rosny’s distant future, nearly all of the planet’s water has been lost to space or drained deep into the earth’s crust. A few communities survive in desert oases. They have adapted remarkably well to this nearly uninhabitable world. Technology is so good, that most of the physical needs of human society are provided almost effortlessly: energy, materials, engineering, transportation, communication are all completely solved problems. But two problems can’t be solved by any technology — the lack of water on the planet, and the frequent earthquakes that obliterate the wells and springs on which people so desperately depend.

The human species is dying out and people know it. Except for some crop plants and a species of intelligent birds, humans are the only carbon-based life that remains. A deep-rooted fatalism has taken over. Suicide and euthanasia are common, and sometimes, when a community’s water runs low, required by law. People are generally willing to embrace death enthusiastically, since they have nothing to live for. Technology has eliminated the need for all labor, and “there was almost no work to be done.”

The human species is dying out and people know it. Except for some crop plants and a species of intelligent birds, humans are the only carbon-based life that remains. A deep-rooted fatalism has taken over. Suicide and euthanasia are common, and sometimes, when a community’s water runs low, required by law. People are generally willing to embrace death enthusiastically, since they have nothing to live for. Technology has eliminated the need for all labor, and “there was almost no work to be done.”

Thus, nothing occurred to disturb the listlessness of these Last Men. Those best able to escape from these doldrums were the least emotive individuals, who had never loved anyone, and had hardly love their own persons… they were the perfect products of a doomed species.

Young Targ and his sister Arva are an exception — they refuse to accept the obvious fate of their species. Rosny describes them as atavisms, throwbacks to an earlier period when the drive to survive was strong. Targ shows his survival instinct when, after an earthquake destroys the water supply of one community, he relentlessly searches for a new source of water. He succeeds and the community is saved. Targ goes on to get married and keep faith in a bright future for his children.

But inevitably the water runs out again. The community initiates a major program of euthanasia to bring the population down. Targ and Arva are unwilling to give up the struggle to survive, and so they flee with their families to find a new home in an abandoned oasis, where the previous inhabitants all committed suicide. Here they try to build a future for their children.

The tension that drives Rosny’s story is the conflict between Targ’s will to live and his growing realization that human life is becoming impossible. The struggle for survival is no longer self-evidently worthwhile, and Targ is forced to justify his desire. “Why would we live?” asks one young woman, who is about to succumb to euthanasia. “Why did our ancestors live? Some inconceivable madness made them resist, over millennia, the decrees of nature… They accepted to live an abject existence… simply so as not to vanish.”

THE MINERAL KINGDOM

The greatest challenge to Targ’s desire to preserve a human future is, however, not the fatalism of his community. It’s the growing dominance of a completely new form of life: “ferromagnetics.” They are unintelligent, slow-moving microbe-like organisms that consist entirely of various forms of iron, and are at the very beginning of their evolutionary history. To the last remaining humans, the earth is dying. But Rosny makes it clear that the human perspective is too narrow; the dehydrated earth is still the source of new life, just as it was four billion years before when the first proto-cells emerged. The “mineral” future of life on earth is continually before Targ’s eyes, but he refuses to accept it for as long as he can.

In the end, Targ can no longer deny it, because he has become the Last Man. His sister, his wife, and his children are all dead. His desperate hope to see the human race reborn is now impossible, and Targ finally accepts the truth:

He thought that whatever remained now of his flesh had been transmitted, in an unbroken line, since the origin of things. Some thing that had once lived in the primeval sea, on emerging alluvia, in the swamps, in the forests, in the midst of savannas, and among the multitude of man’s cities, had continued unbroken down to him. And here, the end!

He finally gives his body, this flesh descended in an unbroken lineage from the beginning, over to the new life of the ferromagnetics.

Rosny wasn’t the first SF writer to consider the evolutionary end of humanity. But, compared to Flammarion’s sentimental mysticism or Wells socially-motivated evolutionary degeneration, Rosny’s vision is brutally cosmic. Humans, despite their technical mastery and undisputed reign over the earth, are not the exception, and they will in the end pass just like any other life.

Read more entries in my post-apocalyptic science fiction series, and my other science fiction reviews.

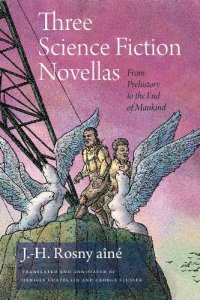

Image Credits: View from Rocknest, NASA Mars rover Curiosity via Wikimedia Commons; Jacket cover illustration by Mahendra Singh, from Three Science Fiction Novellas: From Prehistory to the End of Mankind, J.-H. Rosny aîne, tr. Daniele Chatelain and George Slusser, Wesleyan Early Classics of Science Fiction series.