Camille Flammarion’s Omega: The Last Days of the World (1893)

Whether fiction written early in the 19th century qualifies as genuine science fiction is debatable, but when it comes to the futuristic fiction of the end of the century, there can be no doubt. The nascent genre was quickly becoming popular, and in the two decades before World War I, science fiction became truly engaged with science — particularly the radical scientific discoveries that transformed communication, war, public health, and especially, our place in the cosmos.

Whether fiction written early in the 19th century qualifies as genuine science fiction is debatable, but when it comes to the futuristic fiction of the end of the century, there can be no doubt. The nascent genre was quickly becoming popular, and in the two decades before World War I, science fiction became truly engaged with science — particularly the radical scientific discoveries that transformed communication, war, public health, and especially, our place in the cosmos.

Edgar Allen Poe and Jules Verne were the trailblazers, writing works inspired by contemporary developments in science, which both of them followed closely. Then came the French astronomer and popular science author, Camille Flammarion, the Carl Sagan of his day. His 1893 End of the World novel Omega: The Last Days of the World is a grand future history, with a mystical but secular cosmology deeply rooted in the science of the day. It’s an almost modern work of science fiction, a bridge between de Grainville’s early Gothic apocalypse and the radically new 20th century apocalyptic science fiction of H.G. Wells.

Like Carl Sagan’s Contact, Omega is primarily a didactic novel, intended to convey real scientific concepts in an entertaining, fictional setting. And like Contact, Omega deals with the boundary between the scientific and the mystical, looking for a secular sense of human meaning in the grand scheme of the cosmos. But unlike Contact, Flammarion’s book doesn’t have much of a plot.

APOCALYPTIC VARIATIONS

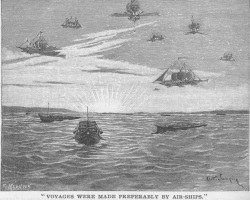

The book opens in the 25th century (or maybe the 24th — Flammarion occasionally mixes them up). Airships abound, the center of world culture is in Chicago, and humans are in regular contact with the Martians and Venusians. But the focus of the story is, of course, Paris. A great crowd is gathered outside the Paris Observatory to hear the latest news about a comet that is on a collision course with earth. Inside the Observatory, scientists are gathered to hear presentations on the likely consequences of the comet. But the meeting quickly develops into an expansive, interdisciplinary discussion of all of the different ways the world could end. One by one, scientists from different fields present their thoughts and detailed calculations for a scenario of the death of the world.

Taking his cue from Edgar Allen Poe, Flammarion’s narrator asks, “This was the unknown, the expectation of something inevitable but mysterious, terrible, coming from without the range of experience. One was to die, without doubt, but how?”

Taking his cue from Edgar Allen Poe, Flammarion’s narrator asks, “This was the unknown, the expectation of something inevitable but mysterious, terrible, coming from without the range of experience. One was to die, without doubt, but how?”

One astronomer argues that the main threat is the heating of the atmosphere by cometary debris. Another agrees, but says the heat will be enough to ignite the atmosphere:

For about seven hours — probably a little longer, as the resistance to the comet cannot be neglected — there will be continuous transformation of motion into a heat. The hydrogen and oxygen, combining with the carbon of the comet, will take fire. The temperature of the air will be raised several hundred degrees; woods, gardens, plants, forests, habitations, edifices, cities, villages, will all be rapidly consumed; the sea, the lakes and the rivers will begin to boil; men and animals, enveloped in the hot breath of the comet, will dies asphyxiated before they are burned, their gasping lungs inhaling only flame. Every corpse will be almost immediately carbonized, reduced to ashes, and the vast celestial furnace only the heart-rending voice of the trumpet of the indestructible angel of the Apocalypse will be heard, proclaiming from the sky, like a funeral knell, the antique death-song: ‘Solvet saeculum in favilla.’

It goes on like this for about half of the book. A medical expert says the main threat is carbon monoxide poisoning. The geologist argues that the earth won’t die for millions of years, until all land is eroded away and rivers cease to flow. The President of the Physical Society argues that the earth will die of cold, as the atmosphere stops trapping heat as it loses water vapor. The Chancellor of the Columbian Academy agrees the earth will die cold, but argues that it will be due to the death of the sun in 20-40 million years.

The discussion isn’t only left to the scientists. Far away from Paris, at the Vatican, bishops, priests and theologians argue over the literal fulfillment of scriptural prophesy. Flammarion then goes on to explore “the history of the human mind face to face with its own destiny,” different historical beliefs about plagues, comets, earthquakes, and volcanoes as signs of the End of the World. There is a clear progression: religious thinking and superstition give way to scientific beliefs about human extinction. By the end of the 25th century, even “Christian thought had gradually become transformed, among the enlightened, and followed the progress of astronomy and the other sciences.”

The discussion isn’t only left to the scientists. Far away from Paris, at the Vatican, bishops, priests and theologians argue over the literal fulfillment of scriptural prophesy. Flammarion then goes on to explore “the history of the human mind face to face with its own destiny,” different historical beliefs about plagues, comets, earthquakes, and volcanoes as signs of the End of the World. There is a clear progression: religious thinking and superstition give way to scientific beliefs about human extinction. By the end of the 25th century, even “Christian thought had gradually become transformed, among the enlightened, and followed the progress of astronomy and the other sciences.”

EVOLUTION OF PERFECTION – *SPOILER ALERT*

After working out the different possibilities for a secular, scientific apocalypse, Flammarion moves on to consider the grand arc of future human evolution. Much like H.G. Wells two years later, in The Time Machine, and Olaf Staepledon in the 1930’s, he builds a picture of a secular human future informed by 19th century discoveries in biology and geology.

As it turns out, humanity survives its encounter with the comet. It is certainly a catastrophe, with many lives lost (medical statisticians estimate 222,633 additional deaths), but the species goes on to survive and evolve into a more beautiful, more perfect form. Human biology and technology progress for hundreds of thousands of years. Eventually humans become capable of telepathy. As they reach their peak, the earth begins to die.

In the final section, Flammarion tells a story of the last human couple clearly inspired by de Grainville’s Last Man. This time the end is a secular one, part of a natural cycle, but Flammarion also steeps it in mysticism. Omegar and Eva find each other in a dead city on a parched plain of the dried-up earth. The ingenious technology for extracting water from the increasingly dehydrated planet is beginning to fail. The couple knows they are doomed, but at the point of death they are visited by the spirit of Cheops, the ancient King of Egypt, who tells them there is no such thing as true death. “Worlds succeed each other in time as in space. All is eternal, and merges into the divine.” The book ends with a view of the rebirth of new worlds from the remnants of our dead solar system.

In the final section, Flammarion tells a story of the last human couple clearly inspired by de Grainville’s Last Man. This time the end is a secular one, part of a natural cycle, but Flammarion also steeps it in mysticism. Omegar and Eva find each other in a dead city on a parched plain of the dried-up earth. The ingenious technology for extracting water from the increasingly dehydrated planet is beginning to fail. The couple knows they are doomed, but at the point of death they are visited by the spirit of Cheops, the ancient King of Egypt, who tells them there is no such thing as true death. “Worlds succeed each other in time as in space. All is eternal, and merges into the divine.” The book ends with a view of the rebirth of new worlds from the remnants of our dead solar system.

During the late 19th century, French writers were bringing the science into science fiction. Jules Verne, J-H Rosny aîné (my favorite), and Flammarion wrote stories that responded to the tremendous scientific developments of the time. Flammarion’s Omega is a major entry in End of the World fiction, defining a central obsession of the genre: “Is not the destiny and sovereign end of the human mind the exact knowledge of things, the search after truth?” Omega lays out a scientifically informed, grand future view of the death of the earth and human extinction, one that left its mark not only on H.G. Wells but also on many writers in the century that followed.

Read more entries in my post-apocalyptic science fiction series, and my other science fiction reviews.

The University of Nebraska’s Bison Books has published Omega as part of its excellent series of classic science fiction.

Image credits: Uncredited illustrations from Omega: The Last Days of the World, Camille Flammarion (New York: Cosmopolitan Publishing Company, 1894).