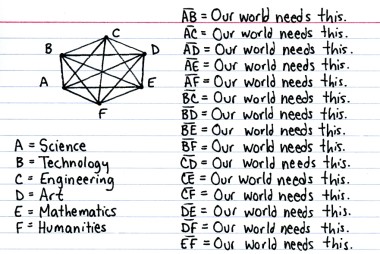

This pretty much sums up my world view.

Like STEM and STEAM, SHTEAM is a lousy acronym; but it is infinitely preferable to the SHAT ME option.

Kelly Heaton’s new exhibition, Pollination, uses the central motif of plant sex to explore subjects from the scientific (colony collapse disorder) to the romantic (human sexual attraction), to the technological (the spread of ideas). And she uses a dizzying array of media to do it.

The show, at Ronald Feldman Fine Arts in New York through October 24, is dominated by The Beekeeper, a huge kinetic sculpture in which bees fly around an illuminated honeycomb rooted in a landscape of floral electronics.

Heaton also created eight perfumes for the exhibition. Bee The Flower is an “artist’s toolbox” for painting your body with perfume and “pollen.” The perfumes, which visitors can smell, include one made from bee-friendly plants and one actually extracted from dollar bills.

Other works in the show include paintings, pastels and sculptures exploring ideas about the changing world of agricultural production and about humans’ “infestation” by electronics.

If you can’t make it to New York to see Pollination, Heaton, who has degrees in both art and science, has also written a book about the show, which is available on Amazon. You can see more of her work on her website.

Most of the oldest surviving art in the world is made of stone. But scientists now believe that the Shigir Idol, a huge, enigmatic wooden sculpture found in a peat bog in Russia in 1890, is twice as old as the pyramids at Giza.

The Idol, which once stood about 15 feet tall, depicts a man with many faces and an elaborate pattern of carved lines.

The sculpture was carbon-dated in 1997 and determined to be about 9,500 years old. However, many scientists disputed the findings, so curators at the Sverdlovsk Museum decided to submit samples for re-testing.

A lab in Germany conducted tests using Accelerated Mass Spectrometry on seven tiny wooden samples. The results indicated the idol was in fact about 11,000 years old, from the early Holocene epoch. It was carved from a larch tree using stone tools.

Professor Mikhail Zhilin, of the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Archeology, told the Siberian Times: “We study the Idol with a feeling of awe. The ornament is covered with nothing but encrypted information. People were passing on knowledge with the help of the Idol.” While the sculpture’s carvings remain “an utter mystery to modern man,” Zhilin said the Idol’s creators “lived in total harmony with the world, had advanced intellectual development, and a complicated spiritual world.”

Ants fascinate humans with their strength, their adaptability and their astonishing ability to work together to achieve goals. Artist Loren Kronemyer enlisted large groups of them to create her 2012 project, Myriad.

Kronemyer draws on paper with pheromones, then releases ants onto the paper. The ants, drawn to the scent, briefly cooperate in completing her designs before going back to their own patterns of movement. The artist explains that her projects explore “the notion of living drawing” as a collaboration showing the interplay of insect and human intelligence. Kronemyer, who has also created drawings with living tissues, says:

“The ant colony is a superorganism, a system with its own intelligence made up of many individuals, and the tissue is a fragment of an individual that is itself made up of many discreet living entities. I sit somewhere in the middle, meddling with both yet at the same time responsible for caring for them and keeping them alive.” (source)

The various works in Myriad are full of life and movement. The image of the brain, in particular, works as a great visual metaphor for a short attention span, or perhaps a sudden realization. Kronemyer, an American who moved to Australia to work with SymbioticA Lab, says that “at a certain point I stopped being interested in just representing living systems, and wanted to work with the systems themselves.” It’s a long way from paint and marble, yet the visual delight of her work keeps it from simply becoming a science-fair project and plants it firmly in the territory of art.

You can see more of Loren Kronemyer’s work at her website.

The most recent guest on This Week in Virology (or TWiV) is none other than our own Michele Banks. Michele welcomes host Vincent Racaniello of Columbia University into her home for an extended conversation about the hows and whys of her science-inspired art.

For those of you who are not regular readers of Michele’s Art of Science series, what I have always found fascinating about discussing art and the process of creation with Michele, is her engagement with the current art world and the history of art, with an honesty and clarity that is quite brave – when so many artists armor themselves (like scientists) against public judgment in overly complex jargon.

I can’t send Michele to everyone’s living room to have that conversation with you; but, thanks to TWiV, I can send Michele’s living room to you.