Two of the most interesting science-related destinations on earth are both garbage-related, so get ready for a garbage-themed two-part post.

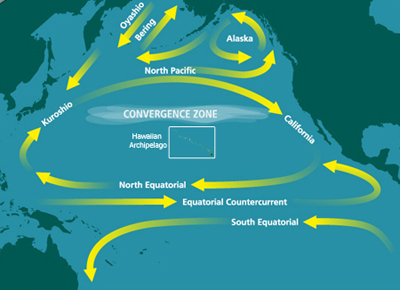

Remember the duckies that floated around the oceans for years? Ocean currents brought them all the way across the Arctic. But ocean currents don’t always push garbage to shore. The currents also create large vortexes from which floating plastic can’t escape. Instead, it all stays within the vortex, and creates a patch of floating waste in the convergence zone.

This is what happened at the Pacific Garbage Patch.

Despite some photos you may have seen, this is not a large patch of floating objects. (In fact, I can’t find ANY reliable and reusable photos of what it ACTUALLY looks like, so you just get a map.)

Unlike the duckies, which retained their duckie shape throughout their oceanic travels, the majority of the plastic in the Pacific Garbage Patch is not shaped like any recognizable objects. It’s mainly plastic pellets, down to microscopic size. The water can look relatively normal on the surface, but water samples consistently show plastic.

As Miriam Goldstein describes in an interview with io9, it’s not entirely clear what the effect is of so much plastic in the ocean, but it’s definitely changing the ecosystem.

It’s also very difficult – logistically – to clean up plastic from such a large and remote area. It’s not close to any particular country, and the garbage comes from everywhere, so whose job is it to clean?

The best solution, of course, is to prevent garbage from ever ending up in the ocean in the first place, and next week I’ll take you on a virtual trip to a place where household waste is being reused in a unique way.

Map from Wikimedia, in the public domain.