Some final observations from Paula Stephan’s provocative book, How Economics Shapes Science (Harvard University Press, 2012):

1) The current incentive structure is creating an inefficient system. The job market for biomedical PhDs has been generally poor for some time now, and it has been getting worse. From the perspective of Deans and established investigators, the system is working beautifully because established scientists are highly productive. But from an economic perspective (and from the perspective of newly trained PhDs), this is a highly inefficient system that relies on cheap, temporary, highly skilled workers with future job prospects that are unlikely to repay the opportunity costs of PhD and postdoc training.

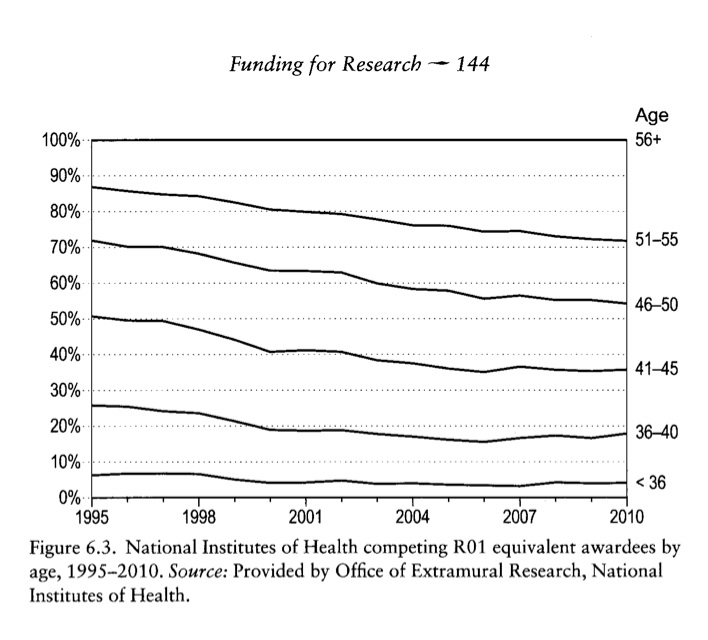

The university research system has a tendency to produce more scientists end engineers than can possibly find jobs as independent researchers. In most fields, the the percentage of recently trained PhDs holding faculty positions is half or less than what it was thirty-three years ago; the percentage holding postdoc positions and non-tenure-track positions (including staff scientists) has more than doubled. In the biological sciences it has more than tripled. Industry has been slow to absorb the excess. A growing percentage of new PhDs find themselves unemployed, out of the labor force, or working part time.