Yesterday, I promised you sexy food and the science behind it. Therefore, crème brûlée. Look at all those accent marks! Sexy, right? And, why not start with eggs – queen of ingredients, bringers of life, denizens of diner griddles, the heart of fluffy meringues, and the soul of silky custards. Crème brûlée is sexy because it is simple. Smooth, creamy custard1 contrasts with a thin, crisp layer of smoky caramel. Every flavor and texture is a balance – creamy and crisp, sweet and bitter, light and deep – harmonizing to enhance and elevate the dish.

Yesterday, I promised you sexy food and the science behind it. Therefore, crème brûlée. Look at all those accent marks! Sexy, right? And, why not start with eggs – queen of ingredients, bringers of life, denizens of diner griddles, the heart of fluffy meringues, and the soul of silky custards. Crème brûlée is sexy because it is simple. Smooth, creamy custard1 contrasts with a thin, crisp layer of smoky caramel. Every flavor and texture is a balance – creamy and crisp, sweet and bitter, light and deep – harmonizing to enhance and elevate the dish.

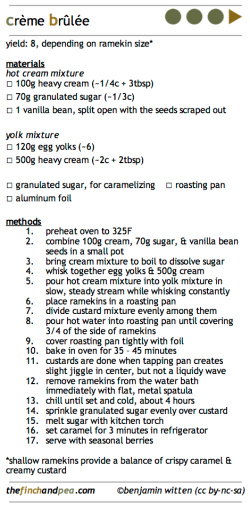

If you want to know the steps to making crème brûlée, use the recipe below (PDF – 115kb). If you want to know how crème brûlée becomes sexy keep reading. The science of sexy can be unlocked by through an understanding of a few properties of these few, simple ingredients.

THE EGG

Crème brûlée is made with egg yolks, and only the egg yolk. Egg yolk has lower protein concentration and more fats than egg whites. These factors cause the proteins in the yolk to clump up more slowly in the yolk. Think of a sunny-side up egg. Proteins normally exist in neatly ordered knots and structures, ready to do their biological jobs. The heat from the pan causes these proteins to unravel. Unlike those neatly organized proteins before we started cooking them, the unraveled proteins can start getting tangled up with each other and forming clumps, like strands of Christmas lights. We call this clumping process coagulation. Proteins clump faster and at lower temperatures in the whites than the yolk, because the whites have a higher protein concentration and lower concentrations of other, interfering molecules, like delicious fats. The short-order cook at your local diner exploits this difference in coagulation rates to give you the fully cooked whites and runny yolk of a perfect fried egg.

The same thing happens in a custard. Egg whites in a custard mean more protein clumping; and more protein clumping means a firmer and less creamy custard. We want silky, creamy, and sexy. So, we only use the egg yolk.

THE MIX

Egg whites normally begin to coagulate at 140F (60C). Yolks begin to coagulate at 150F (66C). Adding milk and sugar will slow the unraveling and clumping of the proteins. The coagulation temperatures will go up to 150F (66C) for whites and 160F (71C) for yolks. Using cream instead of milk adds more fats, further disrupts protein clumping, and raises the coagulation temperature, giving us a softer custard (if science fair taught me one thing, it was graphs are important).

Since we are looking for the creamiest combo we can get, we are going to use yolks and cream. To further ensure that perfect cook for our yolks, we are going let the cream help our egg yolks handle the heat through a process we call tempering. When working with eggs it is always important to heat them slowly. I don’t care if you are making custard, scrambled eggs, or over-easy. ALWAYS HEAT THEM SLOWLY! Rapid heat transfer unravels proteins faster and creates more firm bonds between them. Firm bonds equal rubbery eggs. No one has ever sent back their eggs because the weren’t rubbery enough.

If you heat two eggs to the same temperature, but heat one rapidly and the other slowly, the egg heated rapidly will always have tighter bonds and be less delicate. This is why every custard recipe has that enigmatic direction to slowly pour heated cream into the eggs. Because we are adding only a little heated cream to a lot of egg yolks and mixing2 (tempering), each bit of cream only slightly increases the temperature of our mixture. If our eggs are gently warmed before encountering the more intense heat of the oven, the initial change in temperature for the eggs is less dramatic and the protein clumping is less severe. If we were to put a completely cooled custard mixture in the oven, the initial heat transfer would be more rapid to bring it up to temperature giving you a less delicate custard. But, that isn’t our only trick for handling the heat.

THE BATH

Our mixture of cream, yolks, and sugar now has a starting coagulation point of about 170F (77C). As a result, our custard will reach a state of uniform, silky bonding around 180F (82C) and start to scramble (chef jargon for coagulating the crap out of some proteins) at 190 – 200F (88-93C). A clever and eager reader who has been reading the recipe, might say, “Hold up! The recipe says to bake the custards at 325F (163C). That’s a bit hotter than the scrambling temperature of 200F (93C). Saboteur!” Not so fast. Your oven is set to 325F (163C), but I promise I’ll keep them cooler than that. That’s why we are going to take them swimming.

We are going to put our custard in a water bath, or bain marie. If we slid our custards into a 325F (163C) oven as is, the outside would scramble before the heat had time to reach the center leaving the inside runny and raw. The water bath is there to moderate the heat. Water is a liquid between 32F and 212F(0-100C)3. At 212F (100C)3, the water turns into vapor. Liquid water cannot get any hotter than 212F (100C)3. Any extra heat energy is used to change from liquid to vapor or to heat up the vapor. By surrounding our custard with water that cannot exceed 212F (100C), we are now actually cooking them closer to their coagulation point and can gently bring the entire mixture to an even coagulation. I also like to seal the top of my pan with foil. This traps a cushion of steam in the pan to moderate the heat hitting the top of the custard.

We now have the creamy side of our sexy equation. All that’s left is a little contrast…a little crunch.

THE BURN

It is the caramel layer that puts the brûlée in the crème brûlée. Which means you get to burn something. On purpose. With a torch. Caramel is simply burnt sugar. Sugar starts burning at 320F (160C). For caramel, we normally do a slow burn, typically in a pan, to control the darkness, and, therefore, the bitterness, of the caramel. For the crème brûlée we need a fast burn, because the sugar is sitting on top of the custard4. If we give the heat enough time to get into our custard, it will ruin all our careful work from before. Once again, we are trying to control our heat; and this is why I advocate using a torch instead of the broiler. A torch applies more heat more directly. You burn the sugar faster and with more control, but you won’t heat the rest of the dish. The extreme heat of the torch will melt and start burning the thin layer of sugar in seconds. With our thin crispy brûlée layer in place, our sexy equation is complete.

I am going to take one last moment here to talk about what is not on the ingredients list. Crème brûlée should not be made with chunks of fruit fillings. Ever. This may sound like personal opinion, but I’m right. Chunks of fruit ruin the texture balance and become watery when cooked for long periods. Lovely pieces of fruit turn into unappetizing pockets of steaming mush that over cook the surrounding custard. Save the fruit for an accompaniment.

And, don’t even think about making chocolate crème brûlée. You heard me:

Put! Down! The! Chocolate! NOW!

The amount of starch in cocoa powder makes chocolate a thickening agent. Add it and heat to a liquid (eg, custard) and your mixture will thicken giving you something thick and dense like pudding5 instead of a soft, silky custard. Tasty, but not the elegantly sexy crème brûlée we’re making here.

Hopefully you will walk away from this post with the confidence and knowledge to cook your own sexy custard creations. Remember, with the right understanding of your ingredients, you are only a pan, some tap water, and a torch away from silky, creamy decadence.

CHEF’S NOTES

- The technical term for any heated mixture of milk, sugar, and egg.

- If you don’t mix as you pour, you will get hot spots around the cream that will scramble the surrounding yolk.

- At sea level in an unpressurized system

- Do not try pouring melted caramel over the top. Caramel is viscous and you will end up with a thick layer of hardened caramel instead of the thin crisp layer you get from torching the sugar directly on the custard.

- Or pots du crème.

Can you say anything about the science of pulling your water-bathed creme brulee out of the oven without spilling water all of the top of the custard? For me that’s an almost inevitable point of failure.

Very nice discussion! It’s nice to know why I always screw up fried eggs. And I’m with you on no chocolate in the creme brulee. If you want chocolate, go for the mousse.

My usual trick is to pull the rack of my oven then transfer the ramekins from the water bath to a sheet pan while the water bath is still on the oven rack. At least that way if you slosh water around, it won’t get in your creme brulee.

You know, there are chocolates without thickener ingredients, like chocolate syrup, out there. And what about vanilla beans?

I agree that the water bath is a point of failure for custards, but I’m willing to risk it for good custards. Creme Brule is a peak flavor/mouth feel experience. I first had really good creme brule in a wonderful place on a cliff top overlooking the Pacific in Oregon! Amazing…

1. If you really have that much difficulty removing the custards from the oven, buy a creme brulee kit. They typically include a holding rack which allows you to lift all of the ramekins out of the bath simultaneously.

2. I use real vanilla bean when I have it, vanilla extract when I don’t. The taste is identical. It doesn’t affect the texture of the custard.

3. Say no to chocolate, but yes to trying different flavors of custard. I had a pistachio creme brulee years ago that was amazing.

4. If you’re interested in learning more about the science of egg cooking, the American Chemical Society has a webinar from a year ago which discusses this very matter, dispelling the various myths via actual experiment. Among other things, the speed doesn’t matter- the temperature does. The whole speed thing confuses cooks because it is usually a side-effect of heterogenous heating.

5. I got some fancy colored sugar a few ears ago. It’s usually the kind of stuff people sprinkle on top of cakes for 3 year olds. Out of curiosity, I replaced the usual granulated sugar with it, and have never looked back. The colors are bright and beautiful, and the crunchy layer is somewhat thicker than otherwise. Particularly useful if you have deeper ramekins. Crappy picture here, when I also experimented with black sugar (more boring than I thought): http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_aB5clUoFB2Q/TIQHxEMi8nI/AAAAAAAAAeA/_bcbqe-nBxQ/s1600/photo%282%29.jpg The picture doesn’t do it justice- the colors are bright and playful. The coating of sugar is even- the dye from the sugar simply sits in place as the sugar melts.

Hi! The part about covering with foil, are you tightly covering the dish with the water bath? or, how are you using the foil exactly?

Cover the pan tightly with foil. As the water steams it will dome the foil upwards so that any condensation will run to the outside instead of dripping on your brûlées. The steam trapped inside will help maintain a consistent gentle temperature for the brûlées to cook in.

Egg whites coagulate at higher temperatures than egg yolks. See https://freshmealssolutions.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=65:search-perfect-e and everybody else.